This story was first published in the travel section of the Sydney Morning Herald on Sept 11, 2010.

As the warm afternoon draws to a close, I begin to wonder whether I will ever escape this desert town. Barstow, with its dusty line of strip shops along the route of the old Union Pacific railroad in south-east California, has a corroded kind of charm that you can bear when you know you’re leaving.

The locals aren’t too complimentary, either.

”In Barstow you get all the women together, you still won’t have a full set of teeth,” a guy tells me the night before at the Super J Truck Stop, a few kilometres out of town.

I had been at the truckstop in the early hours, shivering under neon, drinking burnt coffee as I waited for a ride south-east towards Mexico.

The truckers file past in silence, doing their best to ignore me as they head inside to fill up on apple pie and bad TV. For the most part big-bellied midwesterners, they are a sombre bunch. I give up in the early hours. After coaxing a lift into Barstow from a truck stop attendant, I drown my sorrows in an all-night bar.

Next morning I emerge from the bathroom of Denny’s diner feeling dazed and with a numb face after a quick wash with the hand sanitiser. At the city limits, I wait by the freeway, on the old Route 66. The Mother Road, as it is also known, Route 66 passes here on its 4000-kilometre journey from Chicago to Los Angeles. This fabled artery of 20th-century America became synonymous with the spirit of travel and adolescent adventure captured in books such as On the Road.

When I was young, I heard stories from my parents about how they had hitched around England in the ’60s. I wanted to share their enthusiasm but like so many others raised on road movies and the Beats, it was the American landscape that I associated with the romance of hitching.

With his canvas bag and pack of smokes the hero of On the Road, Sal Paradise, seemed the ultimate road warrior, a renegade dreamer who lived by the adage that the journey is more important than the destination.

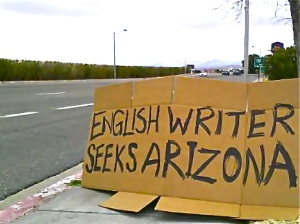

Well past the age when you’re supposed to have abandoned such romantic notions, I make my first attempt at hitching in the US. I have flown into Las Vegas and some friends have dropped me at Barstow. From here I plan to travel via Arizona to the Mexican border.

At the end of the day, I’ve gone nowhere. Hours pass by the roadside. I begin to wonder whether I’ve made a stupid mistake. A couple of online forums I had found suggested travellers are still hitching. The best of them was Digihitch, which contained nuggets of advice including state bylaws as well as testimony from hitchers and rail-hoppers.

The drivers who whiz by are obviously not subscribers and as they speed into the distance, my resolve goes with them. I call to double-check the schedule for the Greyhound bus and I’m about to call it a day when I hear a voice behind me. I turn to see a young man in wraparound shades standing by a truck. He is going to Flagstaff, Arizona, he says. Do I need a ride?

His name is Brook and he is a biologist on his way home to his girlfriend and little boy. And as I watch the desert sweep to the mountains and the sun drop out of the sky, the conversation shifts to the dramatic changes fatherhood has brought to his life.

There are few relationships like that between driver and hitcher, thrown together by chance for a few hours and probably never to meet again. The car becomes their confessional.

A veteran hitcher of five decades who publishes stories on Digihitch, Rex Ingram, believes the chance to positively affect someone’s life, either with your words or by simply lending an impartial ear, is one of the best reasons to hitch.

Ingram, who has hitchhiked through all the US states, writes that the intimacy provided by the automobile is conducive to conducting behavioural therapy on a level only attainable by a psychiatrist.

”I’ve been told of murders and robberies, loves and hates, emotional disturbances of every type,” he says.

Flagstaff is a pleasant college town near the rim of the Grand Canyon. We arrive in a blizzard and Brook drops me at a hostel. After a few days, I look online for a ride further south – it’s now possible to thumb a lift from the comfort of your dorm bed. Social-networking sites such as Craigslist contain sections where you can post notices offering rides or asking for them.

My ad gets a response within a day from a man in a beanie touring the south-west in his VW camper. As we drive to Tucson in the early morning, the hills and canyons of central Arizona are green after the winter thaw. Here and there the tumescent branches of the saguaro cactus rise like alien TV aerials, a cinematic shorthand for the American desert.

My driver, Joel, tells me about riding the rails. In the first half of last century, especially during the Depression, catching free train rides was a common way to travel in the US. Hoboes looking for work climbed aboard freight wagons in the dead of night hoping to avoid a beating from a ”bull”, the name given to the men hired to protect the freight.

A former inmate’s memoir published in the ’20s, You Can’t Win offers some first-hand accounts of this world. Its author, Jack Black, rode the rails in all seasons. In one scene, he describes seeing a young man crushed to death when a pile of timber collapses in his wagon.

No one rides the rails out of necessity any more, Joel says. It is mostly college graduates in search of adventure. ”It’s gutter punk,” he says. ”What a trust-fund kid might do to get his kicks.”

I stay a couple of nights in Tucson. The days are getting hot and in the historic Hotel Congress I sip whiskey sours and read ’30s newspaper articles about John Dillinger, the bank robber and public enemy No. 1 who was arrested here with his gang. As in nearby Phoenix, large areas of Tucson are sprawling suburbs devoid of character. Unlike its neighbour, Tucson makes up for this with a well-preserved downtown, which mixes Spanish-style adobe mansions with art deco Americana.

On my last day here, I wait at a petrol station for a ride along the final stretch – 110 kilometres south to Mexico. A minivan turns up, on the way to the border. The driver wants cash, then crams me in the back beside an old Mexican man with no teeth, sucking on dried apricots. Half an hour later the sky darkens. Streaks of rain bounce violently off the bitumen as I try to recall the Spanish for ”please eat with your mouth shut”.

Many commentators blame the media for the decline in popularity of hitchhiking. The depiction of the psychotic loner, either at the box office or in the news, has struck a chord in the public imagination. Add these fears to an increasingly atomised society, where people feel estranged from one another, and you are left with the impression that hitchhiking is a thing of the past.

These armchair obituaries annoy Ingram, who still hitches from his home in Chino Valley, Arizona. He says his golden age for hitching rides was the ’60s, when his US Marines uniform was an ”open ticket for the road”. But he disputes the idea it has become so much harder, or defunct, as a mode of travel.

”It’s always been hard to get a ride and it’s always been easy,” says Ingram, who once got stuck in Barstow for four days waiting for a lift. ”It’s not the time of year or the decade, it’s the getting out there.”